In an alternate reality where the Hoover Dam was never constructed, the course of history in the American Southwest took a dramatically different path, altering both the landscape and the lives of millions. This story begins in the early 20th century, when the Colorado River flowed unchecked, carving its way through the arid lands with wild and unpredictable force.

The absence of the Hoover Dam first impacted the burgeoning city of Los Angeles. Without the dam to regulate the Colorado River’s flow, the city struggled to secure a reliable water supply. The Los Angeles Aqueduct, designed to draw water from the Owens Valley, proved insufficient for the rapidly growing metropolis. As a result, Los Angeles faced severe water shortages, stunting its growth and forcing city planners to seek alternative sources. Desperate for solutions, the city turned to desalination technology, investing heavily in research and development. By the 1950s, Los Angeles had become a pioneer in desalination, transforming seawater into a vital resource. This innovation, while costly, allowed the city to continue expanding, albeit at a slower pace than in our reality.

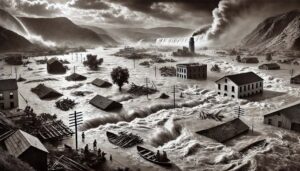

Meanwhile, the absence of the Hoover Dam left the Colorado River Basin vulnerable to catastrophic flooding. In 1938, torrential rains caused the river to swell beyond its banks, inundating towns and farmlands across Arizona, Nevada, and California. The floodwaters swept away homes and crops, leaving a trail of destruction. In response, the federal government launched an ambitious flood control initiative, constructing a network of smaller dams and levees throughout the region. This effort, while partially successful, could not fully replicate the benefits of the Hoover Dam, and flooding remained a constant concern for residents of the Southwest.

The lack of a major hydroelectric power source also had profound implications for the region’s development. Without the Hoover Dam’s turbines generating electricity, the Southwest struggled to meet its growing energy demands. This shortfall hindered industrial growth and limited economic opportunities. In search of alternatives, the federal government accelerated its investment in nuclear energy, establishing a series of nuclear power plants across the West. By the 1960s, the region had become a leader in nuclear technology, but reliance on nuclear power brought its own challenges, including concerns over safety and waste disposal.

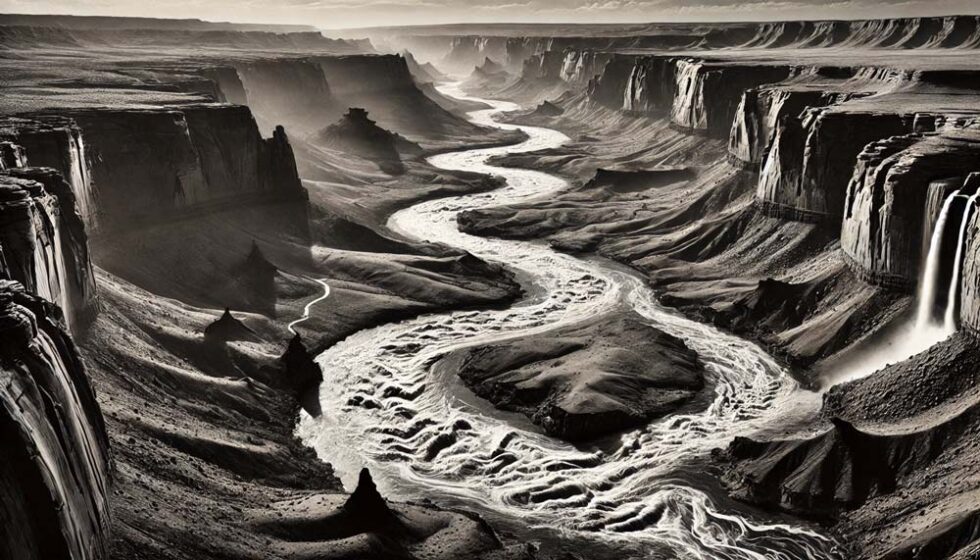

As decades passed, the environmental consequences of the unregulated Colorado River became increasingly apparent. The river’s natural flow patterns led to the creation of vast wetlands in the lower basin, providing a haven for wildlife but complicating agricultural development. Farmers struggled to cultivate crops in the flood-prone lands, prompting a shift towards more resilient agricultural practices. The region became a center for agricultural innovation, with scientists developing drought-resistant crops and advanced irrigation techniques. These efforts helped sustain the Southwest’s agricultural output, but farming in such a volatile environment remained a constant struggle.

By the turn of the 21st century, the Southwest had transformed into a region marked by resilience and adaptation. The absence of the Hoover Dam forced its inhabitants to confront the harsh realities of their environment, spurring technological advancements and fostering a spirit of ingenuity. Los Angeles, once stifled by water scarcity, had become a global leader in sustainable water management, exporting its desalination technology to arid regions worldwide. The nuclear power industry, while controversial, provided a stable energy source, allowing the region to maintain its economic vitality.

No power, no crops.